Also dabbled in medical advertising, why does Google "do not do evil"?

Introduction: If the comparison between Baidu and Google is attributed to corporate ethics, it is undoubtedly the simplest but lazy interpretation. But why can Google not do evil, Google really never do evil?

Source: Sina Technology

The tragic death of young Wei Essie, like another mine pipe, has rekindled years of domestic public resentment over the backlog of fake medical network advertising. So how does the United States regulate and crack down on fake online medical advertising?

A similar search in Google's U.S. for Wei's disease for sci-fi sarcoma reveals that Google also has medical ads, but with a more obvious logo. More importantly, Google's paid ads don't affect the rankings compared to Baidu's iconic bid rankings. At the top of the list are always the relevant encyclodedi and official institutions.

(Google's search ad for the treatment of syringe sarcoma has a clear advertising logo)

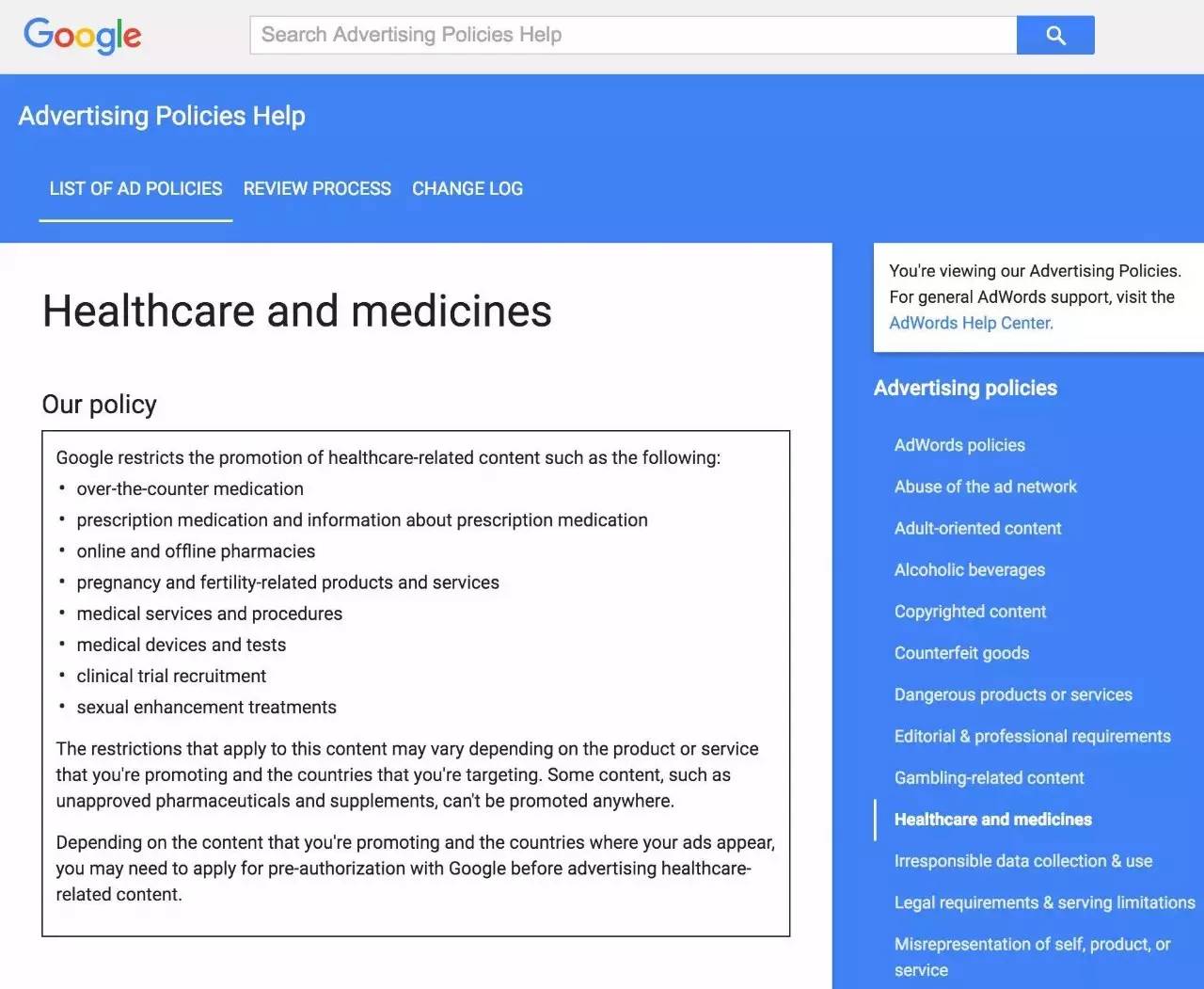

While Google's Adwords ads are also self-service, a query to Google's U.S. search advertising policy reveals that drug ads in Google's U.S. need to be certified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Pharmacy Council (NABP). This means that only government-approved formal online pharmacies and government-approved formal drugs and treatments can run drug search ads on Google's U.S. website.

Coupled with Google's proactive automated ad filtering mechanism, in most cases this can effectively eliminate the possibility of seeing fake medical ads on Google. According to a report released by Google, they blocked a total of 780 million illegal ads and blocked 214,000 advertisers last year, including 12.5 million illegal medical and drug ads involving unsan approved drugs or false and misleading propaganda.

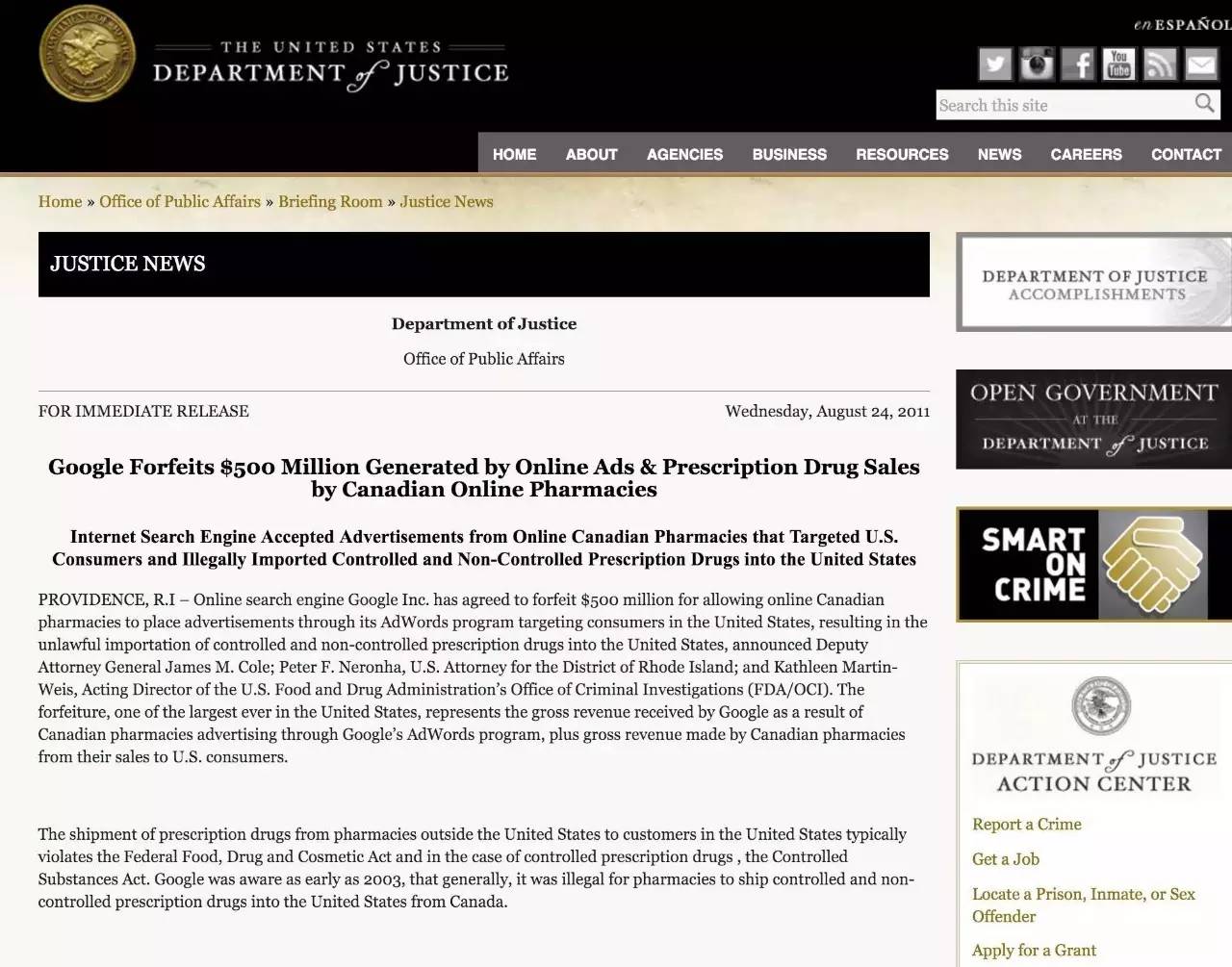

(The U.S. Department of Justice fined Google $500 million)

Google has also faced phishing enforcement

If the comparison between Baidu and Google is attributed to corporate ethics, it is undoubtedly the simplest but lazy interpretation. But why can Google not do evil, Google really never do evil? If you look back at Google's history with fake medical advertising, you might be surprised to find that Google has also fallen too high on the issue and has been severely punished. But it is for this reason that Google can always feel the encouragement from behind, and constantly improve its advertising review mechanism and employee ethics.

Back in 2003, Google was questioned by three different congressional committees over online drug advertising. In July 2004, just a month before Google went public, Sheryl Sandberg, Google's vice president of global online advertising, traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify on the issue as U.S. senators planned to pass two bills regulating online pharmacies. The current Facebook COO said at the time that Google would use a third-party certification service to scrutiny Internet medical and pharmaceutical advertising.

But the series of negative events that followed showed that the world's largest search engine was occasionally embroiled in negative news, even though Google executives had long been aware of the problem with illegal drug advertising. The David Whitaker affair, which broke out in 2009, gave Google its first image on the issue, making it truly aware of the dangers of fake online advertising and the sense of responsibility of search engines to the public. Also that year, Baidu was exposed to false medical advertising.

In August 2011, just the month Google announced its acquisition of Motorola Mobility, Google settled with the U.S. Department of Justice over illegal online pharmacy advertising, for which Google paid the highest corporate fine of $500 million at the time. The U.S. government has long been known for its "tough-heartedness" in punishing corporate infractions. Google's fine record has long been broken by two auto companies. In 2014, Toyota was forced to settle a $1.2 billion settlement with the U.S. government for concealing the accelerator problem. However, the new fine record is no doubt owned by Volkswagen. Volkswagen could end up with a $18 billion fine from the U.S. government after 600,000 diesel cars were blown up late last year.

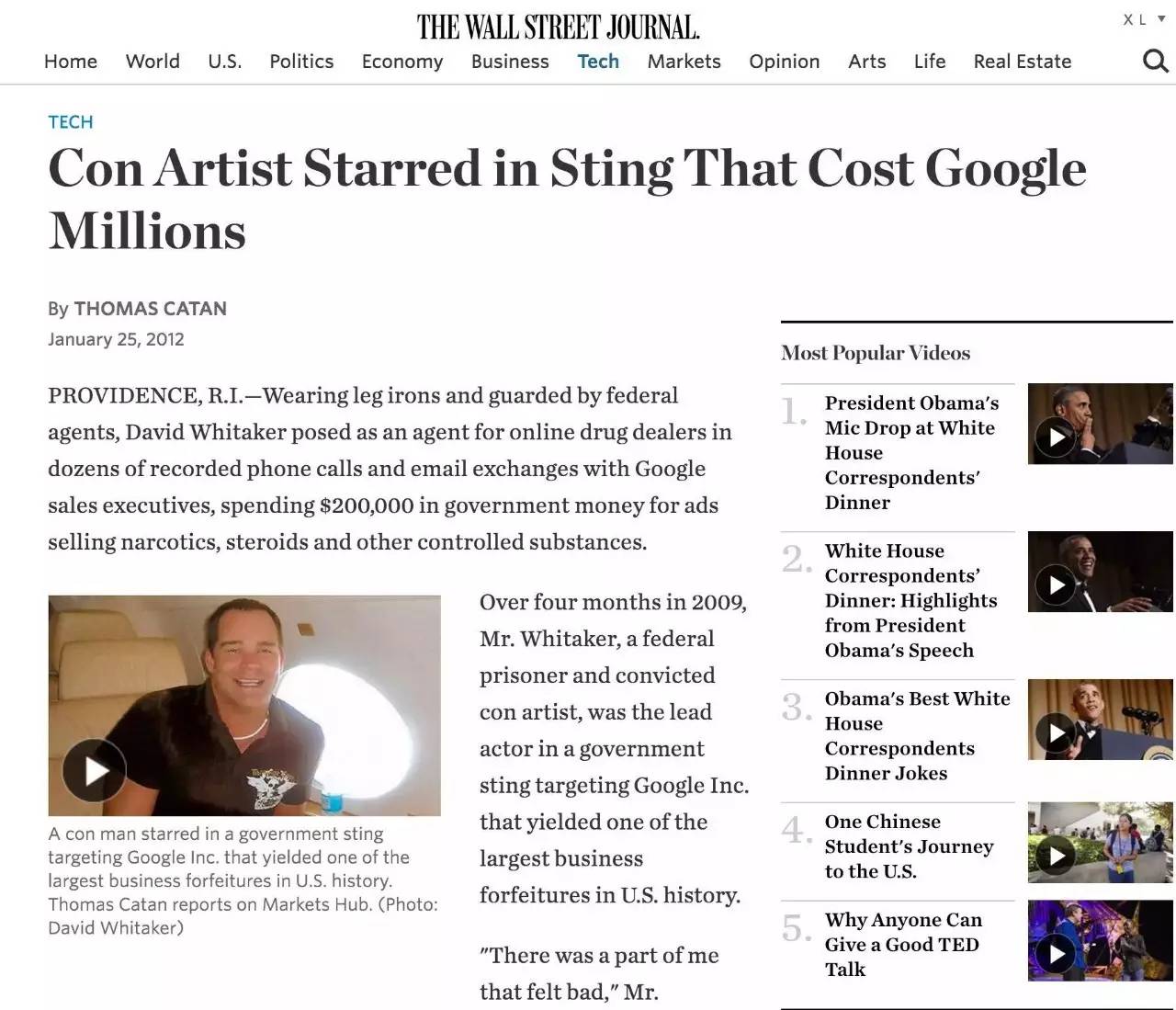

(The U.S. government and the fake drug dealer led the phishing enforcement against Google))

Whitaker, an American counterfeit drug dealer, has long sold fake drugs to U.S. consumers online, falsifying growth hormone and steroid drugs with vegetable oils and protein powders, and selling a bottle of steroids for up to $1,000 or even worthless purified water. He faces up to 65 years in prison (he was 34 at the time) after being extradited from Mexico to the United States in 2008. In exchange for a commutation of his sentence, Whitaker confessed to federal investigators that Google ad sales staff had offered to help him avoid Google's filtering mechanism and run fake drug ads online, knowing it was illegal.

Given Google's good public image, it was clear that his confession alone could not be used as a valid confession, which was hard for even the judiciary to believe at the time. As a result, Whittaker, who did not want to die in prison, worked with the U.S. judiciary to complete one of the most famous fishing investigations in the history of fake drug advertising in the United States. The justices forged a new identity for Whitaker, Jason Corriente, the CEO of a non-existent online advertising agency, in an attempt to get the fraudster to take legal action against Google over how he worked with Google's advertising sales staff to sell counterfeit drugs.

By running $20,000 a month in ads, Whitaker is represented by Google's designated advertising customer service. In several phishing investigations and forensics processes, Google Customer Service actively helped Whittaker optimize, analyze, select and purchase keyword ads, and even helped him make a change to his website, masquerading as a medical information site through Google's automated review mechanism and then reverting to buying options by temporarily removing home drug ads and buying buttons.

The phishing law enforcement, which cost the U.S. judiciary $200,000, ultimately cost Google $500 million in sky-high fines. To prove that this was not a rat behavior by individual Google employees, the U.S. justice agency directed Whitaker to work with customer service representatives in Google's California, Mexico and China regions to run illegal ads related to steroid drugs, and even the tightly controlled abortion drug methadone and psychotic drugs.

The Wall Street Journal, Wired and other well-known media with "this professional fraudster let Google lose $500 million" in-depth coverage of the fishing law enforcement that made Google face. Whittaker eventually reduced his sentence from the original 65 years to five years with a "significant achievement." Although he could not die in prison, the counterfeit drug cheat could face up to $10 million in compensation from former victims of counterfeit drugs.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal at the time, Peter Neronha, the US attorney general, revealed that some Google executives were aware of illegal pharmacies running search ads on their websites. "Based on the documents we reviewed and the witnesses, we know that Larry Page himself knew." The comments were clearly shocking and had a serious impact on Google's image of no wrongdoing, which Google vehemently denies.

(Google's policy on medical search advertising)

Constantly improve the supervision mechanism of medical advertising

After the popularity of the Internet, search engines have become not only the main source of information for people, but also an important way for them to seek medical treatment. Back in 2010, Google estimated that 100 million Americans had 4.6 billion health-related keyword searches that year. According to a Pew survey that year, as many as 60 percent of U.S. adults search the Internet for health information, and 60 percent of Internet users believe that searching for information can affect their health decisions.

Because of the high cost of medical care in the United States, many unseconded patients choose to buy controlled prescription drugs from online pharmacies abroad in order to reduce the cost of seeing a doctor. From 2003 to 2009, Google provided advertising support to online pharmacies in Canada and Mexico to help them run and optimize Adwords ads, according to a settlement between Google and the Justice Department. This not only helps them sell drugs online to U.S. consumers, but also opens up the possibility of illegal access to prescription drugs and substance abuse.

Since 2009, the U.S. government has stepped up investigations into illegal online medical advertising, and Google has been refining its advertising controls ever since. In 2009, the FDA's Drug Marketing, Advertising and Communications Service (DDMAC) sent a letter to 14 pharmaceutical companies arguing that their drug search ads were misleading and only describing the benefits and the risks of not adequately disclosing side effects.

At the end of that year, the FDA conducted a week-long joint investigation with other government agencies, finding that 136 websites involved the illegal sale of unapproved or misn marked drugs to U.S. consumers. Based on the findings, the FDA then sent warning letters to the site operators and asked Internet service providers and domain registrars to terminate the services.

It was that year that Google began taking steps to stop online pharmacies from illegally selling prescription drugs to U.S. consumers. Starting in 2010, all online pharmacies that run drug search ads on Google must be certified by the U.S. government as an Internet Pharmacy Practice (VIPPS), and online advertisers of prescription drugs must be certified as online advertising by the U.S. Pharmacy Council (NABP). Microsoft Bing and Yahoo then implemented similar policies in June of that year.

Under rules implemented by the U.S. Pharmacy Council in 2014, only drug sites that comply with local and local regulations can register domain names and provide services, meaning licensed online pharmacies in other countries cannot sell prescription drugs to U.S. consumers. In the same year, Google announced a $250 million dedicated fund to crack down on "illegal online pharmacies" while increasing the display of content related to prescription drug abuse and working with legitimate pharmacies to combat the marketing of illegal pharmacies.

The U.S. government's campaign to crack down on fake drug ads also includes a variety of nutritional health-care ads. In June 2012, the FDA ordered Google to block all ads in the U.S. that offer detox and health care products, meaning that many health products that sell as "detoxifying and removing heavy metals from the body" will not be able to run ads on Google. It's worth noting that the FDA didn't hold a hearing, nor did it inform the companies in advance or afterwards, or even give them a chance to complain and explain.

Global Health Center, a detox health care company, is a longtime partner in Google's search ads, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars a year on Google. As a result of the sudden blocking of their advertising accounts, their sales plummeted 25-30 per cent in the following week, losing $70,000 in revenue in a month. Google only provided them with an explanation a month later because the FDA considered all over-the-counter antidotes to be "dangerously misleading" and potentially physically injurying consumers, and asked Google to block all drug ads involving "heavy metal detoxes."

Want to share your experience and experience in hospital management and industrial policy with friends? Please send it yxjzhiku@126.com and look forward to your contribution。

Go to "Discovery" - "Take a look" browse "Friends are watching"